Back in the 1990s, while working with the Press Trust of India (PTI), I was approached by a media institute to teach a subject in journalism. They were offering a one-year Diploma in Journalism and Mass Communication and believed my experience could add value to their program.

Initially, I was hesitant. Though I had been a field reporter deeply immersed in journalism, I had never studied it formally. Before stepping into the role of a teacher, I felt it was important to understand what a structured journalism course entailed. So, I enrolled in a one-year PG Diploma myself to prepare academically.

Soon after, I began teaching Print Journalism—and it turned out to be a deeply fulfilling

experience. The students of that era were passionate, curious, and genuinely engaged with news, writing, ethics, and analysis. For them, having a teacher still active at PTI meant access to real-world insights, and they came to class hungry for feedback and improvement. Their energy made it a two-way learning experience and reinforced my belief that journalism is best taught not just through books, but by those who have lived it.

Many of those early students are today editors and media leaders—a distinct, driven generation shaped by mentorship and exposure to the field.

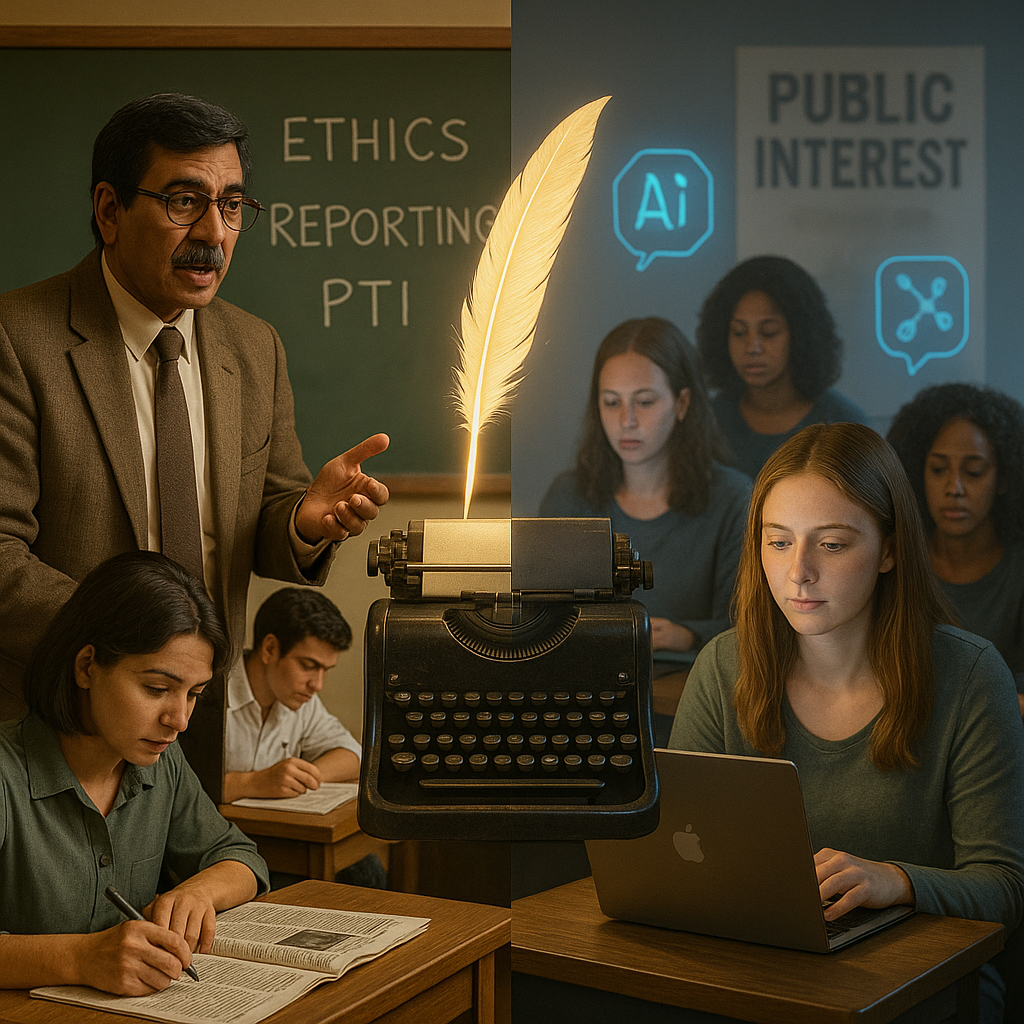

Fast forward to today—and the contrast is stark. We’re in the AI age, where tools can write, edit, and fact-check, but the human essence of journalism often feels sidelined. Students today are digital natives, more fluent in prompts and platforms than in current affairs or investigative reporting. Everyone wants to start with reels—but the foundation of content, credibility, and curiosity is fading.

Now, teaching often means reminding students that journalism isn’t just about algorithms or clicks. Its still about courage, integrity, and storytelling that serves the public interest. Technology can assist—but it cannot replace human judgment and ethical instinct.

Sadly, many journalism programs remain trapped in outdated curricula, taught by academically qualified but industry-disconnected faculty. The shift under the New Education Policy (NEP) toward a liberal, multidisciplinary model—though well- intentioned—risks diluting core journalistic training. While subjects like Political Science or Psychology can enrich journalistic insight, they cannot replace essential skills like reporting, writing, ethics, and media production.

This imbalance between academic breadth and professional depth leads to graduates who may be knowledgeable—but not employable. Meanwhile, the media industry is evolving rapidly, demanding specialization, digital fluency, and hands-on experience. Yet academic models are becoming more theoretical and generalized.

For several years now, the UGC has advocated for the appointment of “Professors of Practice” in universities—professionals who may not hold a Ph.D. but bring significant media industry experience. The idea is to bridge the gap between academia and real- world practice in media education. But how many universities have embraced this initiative? The numbers speak for themselves—and they’re far too few.

The real crisis in Indian journalism education is not one of intention, but of inertia. Universities must urgently realign with industry need-blending foundational skills with

new technologies and interdisciplinary context, without losing focus on what journalism truly is.

Only then we can prepare a generation that is not just degree-holding—but a newsroom-ready and future-ready.